- Home

- Sarah Knights

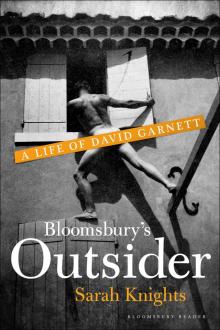

Bloomsbury's Outsider

Bloomsbury's Outsider Read online

BLOOMSBURY’S OUTSIDER

A Life of David Garnett

SARAH KNIGHTS

For Tony and Rafael

Contents

Part 1: Constance

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Part 2: Duncan

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Part 3: Ray

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Part 4: Angelica

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Part Five: Magouche

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Afterlife

Photographs

Acknowledgements

Select Bibliography

Reference Abbreviations

Index

Footnotes

A Note on the Author

Part 1

Constance

Chapter One

‘Alas and alack, I have married a Black.’

‘Oh damn it, oh darn it, I have married a Garnett.’1

This interchange between Constance (née Black) and Edward Garnett, David Garnett’s parents, was more than affectionate banter. They both believed there was such a thing as a ‘Black’ or a ‘Garnett’ with definable characteristics. David remarked: ‘My father believes in heredity and has a passion for explaining people by their grandparents. “That’s the old Willoughby horse-thief strain coming out in her,” he will say […] when some female guest has walked off with a book.’2 David inherited this belief, and like Edward, perceived regional influence upon character. It seemed entirely logical to him that the famous ‘Garnett obstinacy’ hailed from the Yorkshire Garnetts, that his passionate disposition stemmed from the Irish Singletons and that his earthy rationalism was acquired from the Scottish Blacks.

Like Edward and Constance, David considered himself a congenital outsider, attracted to experimental living, to life beyond the mainstream. He liked to define himself in terms of genetic inheritance and evolution: nature as opposed to nurture. Darwinism was a highly convenient belief system, rational and scientific, and if one had inherited certain surviving characteristics, then good or bad, one couldn’t do much about them. Although David despised organised religion and did not believe in any afterlife in the religious sense, he did believe there was another kind of life after death:

We have reason to believe that every living creature is a fresh permutation of ancestral genes which determine its individuality. Half of the possible genes are passed on to the new individual from each parent, half are discarded. The heredity constitution which results is infinitely more important than education or experience.3

Thus David’s forebears were a source of considerable pride. His mother’s paternal grandfather, in particular, was much admired. Born in Scotland in 1788 to a family of fishermen, Peter Black commanded the first regular steam-packet to St Petersburg, built two steamships which sailed between Lübeck and St Petersburg, and was to embark on a career in the Russian navy when he died in 1831. Constance was the daughter of his son, David Black, a dour Brighton solicitor, who had married Clara Patten, a sweet-natured and well-read young woman. The sixth of their eight children, Constance was born in 1861.

Constance was earnest, wore steel spectacles over her pale blue eyes, had a fair complexion and light brown hair worn in a bun on top of her head. According to David Garnett, she was ‘conscious of being more intelligent than the majority of people and, all her married life, of being more intelligent than my father’.4 Constance gained the equivalent of a First in Classics from Newnham College, Cambridge in 1883 (when women were not formally awarded degrees). She was extremely literal, firm in her convictions, independent and adventurous; she disliked luxury or ostentation and loved the countryside. An active Fabian, she narrowly avoided being proposed to by George Bernard Shaw, who was at the time too poor to marry.

David also inherited many Garnett characteristics, the most obvious being his grandfather’s slow, deliberate vocal delivery. Dr Richard Garnett was the grandson of a Yorkshire paper manufacturer and son of the Reverend Richard Garnett, philologist, who in 1838 became Assistant Keeper of Printed Books at the British Museum. Despite an almost complete lack of formal education, Dr Richard Garnett (as he was called to distinguish him from his father) was a considerable scholar; he became Superintendent of the Reading Room in the British Museum, contributed significantly to the Dictionary of National Biography, and his poem ‘Where Corals Lie’ was set to music by Elgar. He is best remembered for Twilight of the Gods, tales of pagan fantasy imbued with dry humour. Such was Dr Garnett’s stature that his obituary in The New York Times stated: ‘No one was better known to the English writing world.’5

David Garnett’s paternal grandmother, Olivia Narney Singleton, was of Anglo-Irish protestant stock, from what David called a line of ‘warm-hearted, passionate, lavish, open-handed libertines’.6 Six years younger than Constance, Edward was born in 1868, and with his five surviving siblings, was raised in an atmosphere of Victorian respectability combined with complete liberality of opinion. Edward was a tall, lanky, curly haired man who loved to tease and was always amused by anyone taking themselves too seriously.

Far from being a stereotypical Victorian couple, Constance and Edward lived together before their marriage in 1889. David felt no need to rebel against his parents: he had no reason to counter Victorian mores because they had done it for him. Instead, he felt immensely grateful to them not only for bestowing upon him what he believed to be their innately remarkable qualities and values, but for giving him unconditional freedom and love. ‘I was lucky enough’, he commented, ‘to find very little in my parents’ beliefs which I had to jettison.’7

Edward early revealed his metier as an exemplary and inspirational publishers’ reader. His grandson Richard (who knew him) considered Edward ‘a congenital outsider, never accepting received opinions and original in all his literary judgements’.8 As his career progressed, Edward’s discernment and advice was invaluable to many talented writers, including D.H. Lawrence, Joseph Conrad, John Galsworthy, W.B. Yeats and H.E. Bates.

While Edward worked in London, Constance remained in the country at Henhurst Cross near Dorking in Surrey. There she began to learn Russian, inspired in this endeavour by her friend Felix Volkhovsky, the Russian revolutionary and man of letters. From these beginnings Constance launched a distinguished career translating Russian literary classics into the English language.

Constance worked at Russian throughout her pregnancy. From her parents’ house in Brighton where she had temporarily moved to be attended by the family doctor, she wrote to Edward in February 1892 expressing her hope that the child would be free from ‘Black coldness’ and ‘Northern Garnett obstinacy’. Instead she wanted him (for she seemed certain it would be a boy) to be a ‘warm-blooded i

mpulsive romantic independent muddle-headed boy – full of spirits and sympathetic – nearly all his father with only the smallest grain of his mother’.9

David Garnett was born on 9 March following a long labour and difficult delivery in which chloroform and forceps were employed. He was a large baby, weighing 9¾ pounds. The nurse commented: ‘I’ve known bigger babies & prettier babies, but never such a cute one, as soon as he was born he lifted up his head & looked about him.’10 Dr Richard Garnett (who wrote about astrology under the anagrammatic pseudonym ‘A.G. Trent’) lost little time in commissioning a horoscope for his grandson. It recommended that David should refrain from public life, live in Brighton and take as an occupation something relating to the sea. It did not, however, predict his life-long sea-sickness.

Edward’s sister Olive Garnett declared her nephew ‘a pretty little fellow & very “manly” […]. He has the most innocent and confiding & altogether winning smile I ever saw in a baby.’11 David was a pretty little fellow, blond-haired and blue-eyed. But some months after his birth Constance noticed something wrong with his eyes. Perhaps resulting from the forceps delivery, David had defective eye muscles which prevented him from looking out of the corners of his eyes. As an adult, this was one source of his charismatic charm, for he would turn his head sideways, bestowing his full focus on whomever he was with. ‘Many people’, remarked his son, Richard, ‘found his candid gaze most attractive.’12

The infant David liked to tease, alarming Constance by pretending to pick up a pin and clench it in his fist. She tried to make him relinquish it, only to find his hand empty. Little David was so enamoured of Randolph Caldecott’s illustration of Baby Bunting in his rabbit-skin cap that a rabbit-skin cap was made for him. In consequence, the village boys called him ‘Bunny’, and the name stuck. It was used by almost all his friends and relatives, a name which suited him in all stages of his life. Rather than compromising his masculinity and dignity, or infantilising him, it seemed to grow with him, softening his stature, gravitas and occasional pomposity.

On New Year’s Eve 1893, when Bunny was twenty-one months old, Constance left him in the care of Edward’s sister, May, while she travelled to Russia. There were several reasons for this momentous journey, but it stemmed from Constance’s and Edward’s friendship with Sergey Stepniak, to whom they had been introduced by Volkhovsky shortly after Bunny’s birth. Having arrived in England in 1884 as a political refugee, in 1890 Stepniak founded the Society of Friends of Russian Freedom. He was a powerful and charismatic figure, committed to ending Russian autocracy and the iniquitous exile system. Moreover in 1878 he had assassinated General Mezentsev, St Petersburg’s repressive and cruel Chief of Police. Despite a sometimes fierce countenance, Stepniak had a gentle charm and affectionate nature, and was greatly taken with Bunny, who liked to carry his toys and pile them upon Uncle Stepniak’s knee. When Edward whimsically commented that Stepnaik was the offspring of a goddess and a bear, Bunny exclaimed, ‘ “That bear that was Uncle Stepniak’s Dad was a good bear” ’.13

Stepniak encouraged Constance in her translating, and she began to experience a sense of vocation for both translation and Russian literature. In consequence, she wanted to see Russia herself and to get a feel for the language and atmosphere of the country. As her grandson and biographer Richard Garnett suggests, Constance’s decision to visit Russia may have been of underlying benefit to Stepniak, who ‘had need of innocent-looking emissaries to carry letters and books that could not safely be sent through the censored mails and perhaps also to take money […] to help Russian political prisoners and exiles to escape’.14

Her bravery and fortitude in undertaking this expedition cannot be exaggerated. Not only was she a woman travelling great distances alone, to a remote country (and on potentially subversive business) but she had a weak constitution. Throughout her childhood tuberculosis of the hip confined Constance to long periods in bed. She suffered from migraine and was extremely short-sighted. Though physically frail, she was emotionally and intellectually robust, and like her grandfather, Peter Black, something of a pioneer. As she hoped, her Russian expedition enhanced her strengths as a translator, leading Joseph Conrad to conclude: ‘Turgeniev for me is Constance Garnett and Constance Garnett is Turgeniev.’15

Later, Constance questioned how she had the heart to leave Bunny for almost two months at that young age. While she was away he would take out her photograph from the drawer, murmuring, as he kissed it, “My mummy gone Russ”.16 But he was always proud of her work and influence, and told her, during the Great War: ‘You have probably had more effect on the minds of every-body under thirty in England than any three living men. On their attitude, their morals, their sympathies […]. I think [Dostoevsky’s] The Idiot has probably done more to alter the morals of my generation than the war or anything that happens to them in the war.’17

Constance coped with travelling, propelled by ‘a passionate longing for adventure’, but passion, in the sexual sense, had fallen from her marriage after Bunny was born.18 Constance seems to have accepted that her libido would not return and that, as her doctor informed her, she must ‘expect to feel middle-aged’.19 A few weeks after Bunny’s birth, running for a train, she experienced what was probably a prolapsed uterus. She was told to rest and prescribed an internal ‘support’. Feeling that ‘one side of my passion seems to have died away’, she worried that Edward would doubt her love. In an astonishingly compassionate and understanding letter, she effectively released him from the ties of conventional faithfulness: ‘I want to make you happy without clogging you and hampering you as women always do. I know and see quite clearly that in many ways we must get more separate as time passes but that need never touch the innermost core of love which will always remain with us.’20

If physical passion no longer bound them, Edward and Constance were united in their affection for both Bunny and The Cearne, the isolated and idiosyncratic house they created. With the aid of a bequest from Constance’s father, The Cearne was designed by Edward’s brother-in-law, Harrison Cowlishaw, an architect working in the Arts & Crafts tradition. Edward and Constance independently viewed potential sites, and to their surprise found they both selected the same spot. They were attracted to a rather remote and inaccessible plot near the village of Limpsfield, on the Surrey-Kent border, offering a magnificent view to south and west. Shielded by woodland, it also provided privacy and solitude. Bunny later recalled visiting the site, carried aloft on Stepniak’s shoulders, from where he saw the building’s great rafters, bare against the sky.

The Cearne was constructed in an L-shape, with immensely thick walls, heavy, hinged wooden doors and enormous inglenook fireplaces. D.H. Lawrence perspicaciously described it as ‘one of those new, ancient cottages’,21 and perceived ‘something unexpected and individualised’ about it.22 Although in ethos it complied with Arts and Crafts traditions of simplicity in design and integrity in materials, it didn’t quite fit the Arts and Crafts mould. It was too simple in style, too medieval, too cold and too uncompromisingly stark. It had the benefit of an upstairs bathroom (though the water closet was housed outside the back door), but generally lacked in comfort, causing Edward and his guests to draw their chairs deep into the inglenook to warm themselves against ever-present draughts. Bunny adored The Cearne: ‘How I love the place! I love every twig, every stone, everything’, he later eulogised. ‘How well the place fits me!’ ‘Coming home is like slipping on an old pair of downtrodden slippers.’ He roamed the surrounding countryside which became an extension of the house itself: ‘There is nothing I don’t know when I’m at home about the place, it is all absolutely familiar. I know the surface of the ground, the stones the roots, even the molehills. When I go into the wood I know all the trees.’23

As a boy, Bunny was solitary but not lonely, spending hours contentedly wandering the countryside, absorbed in flora and fauna. Even so he was conscious that he and his parents were ‘outsiders’, set apart from the villagers and from village l

ife. Instead, the Garnetts both attracted and were absorbed into a growing community of like-minded free-thinkers, which gradually drifted into the neighbourhood and whom Bunny later labelled ‘the Limpsfield intelligentsia’.24 Among this remarkable group were John Atkinson Hobson, the radical social theorist and economist, his wife, Florence, a campaigner for women’s rights, and Edward Pease, secretary of the Fabian Society. The community also attracted Constance’s circle of Russian exiles, who settled nearby at what was to become known as ‘Dostoevsky Corner’.

Having moved into The Cearne in February 1896, Constance and Edward filled the interstices of their marriage in different ways. Constance was fulfilled in her role as a mother and by her work as a translator. But Edward, who spent much of the week in London, needed more: he required someone to supply the physical love which Constance no longer gave. He had fallen in love with the artist, Ellen Maurice ‘Nellie’ Heath, who, by 1899, had become his mistress (though they did not live together until 1914). While this label reflects Nellie’s social position, it does not adequately represent the place she occupied in the hearts of Bunny, Constance and Edward. Constance seems to have positively encouraged the association – Nellie later told a friend that it was she who first mentioned the possibility of a relationship with Edward.

Nellie, who had been raised in France by her widowed father, Richard Heath, a devout Christian Socialist, came to England to study painting under Walter Sickert. Bunny said of her: ‘The first impression was of extraordinary softness, a softness physically expressed at that time in velvet blouses and velveteen skirts; a softness of speech and a gentleness of manner and disposition.’ He added that the softness was underpinned by ‘an iron willpower’, a necessity given Nellie’s social position as Edward’s lover.25 Bunny’s cousin Rayne Nickalls recalled receiving a warning from her father, Robert, about Edward and Nellie living together ‘in open defiance of the conventions’; ‘people talked and he would not like me to be mixed up in anything of that kind’.26

Bloomsbury's Outsider

Bloomsbury's Outsider